Their names, when spoken out loud, transport you to a quiet corner of an old English orchard.

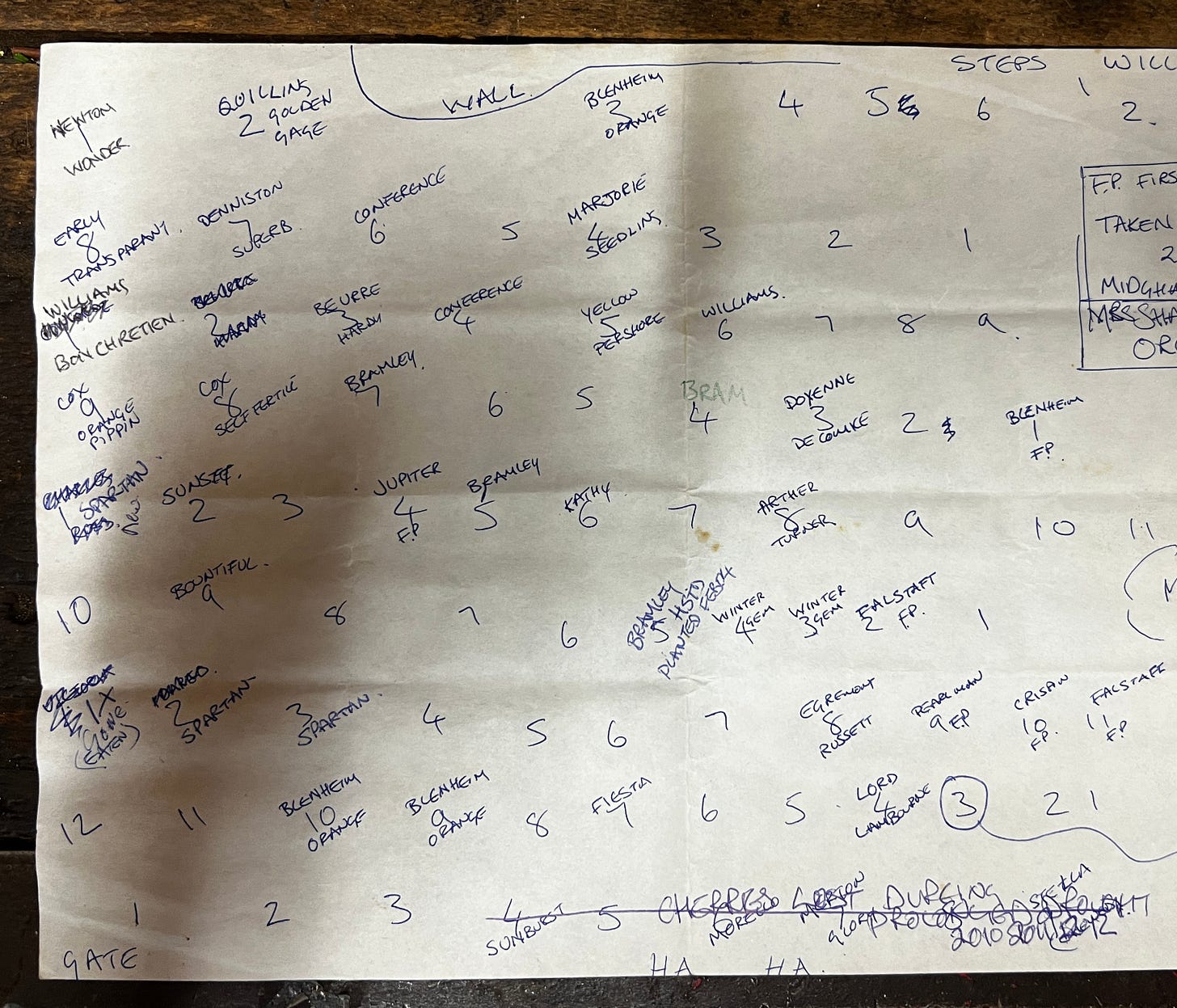

Lord Lambourne, Jupiter, Bramley, Fiesta, Beurre Hardy, Blenheim Orange, Early Transparent, Cox’s Orange Pippin, Winter Gem, Falstaff, Bountiful, Spartan, Egremont Russet, Crispin, Sunset, Newton’s Wonder, Pearl, Ouillings Golden Gage, Marjorie Seedlings, Denniston Superb, Yellow Pershore, Doyenne de Comice, and Williams.

Underneath an old arch of white wisteria, down a set of stone stairs, a crow sits on one of the wooden posts, watching me intensely as I walk through the lines of lichen-covered fruit trees. It’s very quiet here.

The old ivy covered pillars from the original entrance to the old stately home that once stood here stand silently as they have for centuries. A reminder of what was once here and those that were once part of it.

Just myself and my thoughts. A place for contemplation. A place to tell the bees the news and if you are lucky, ripe fruit to pick from the tree. Plums eaten whole, the stone spat out into the undergrowth, soft ripe pears that when bitten drip juice down your chin and apples so perfumed and crisp, you might never have thought it possible. I can hear the buzzards and kites call from high up overhead, watching the movement of the long grasses as I pass through for signs of escaping mice. The trees here were planted decades ago by John. He has looked after them for all these years, never once using any pesticide or fertiliser. The windfalls at the end of the season are what fertilise the ground here. The last of the fruits that the winds knock from the trees after harvest, left to decay and nourish the soil for next year. There are some nets around some of the trunks, to keep some of the pests from climbing and making a home in the branches, but that’s about it.

These trees are loved dearly by many.

They have stood here for decades. They face south, looking over quiet meadows and hills surrounded by long grass and wildflowers. Waist-deep foxtail grass, sedge and rye grow wild here, untouched by anything mechanical until the summer draws to a close. The cattle are hopeful of the windfalls that might come their way when it’s time to harvest. One young bullock last year, possibly tipsy from the fermented windfalls made the bold move and escaped looking for more. He spent a day or two wandering around the orchard before begrudgingly allowing himself to be coraled back into his field.

There are lines of Linden trees in the distance, marking out the driveway, winding its way quietly through the fields, from the stone eagle-topped posts that guard the old ornate wrought iron gates that English Heritage has put a preservation order upon, leading up about half a mile up to the gates to the house.

In the distance is a huge, proud Wellingtonia, one huge bough broken off by a lightning strike. There are pheasants, rabbits, muntjac and roe deer. The young deer are so inquisitive that they stop and stare at you before their instinct takes over and they run. Two wooden bee hives sit in the corner of the orchard, protected from the wind by an old wall. It’s crumbling now, built hundreds of years ago by those who once worked on this historic estate. The wall surrounds an old cemetery, full of headstones bearing names from the long distant past. There is a Jethro Tull who died in 1657, carved in the Romain du Roi typeface, still legible after centuries amongst the blackthorn and oak. A quiet resting place for sure

The honey bees that we introduced here early in spring have been busy, pollinating the pink and white blossom, feeding themselves, collecting pollen for their stores, and filling the frames with honey. Our fruit yields thanks to these little creatures will hopefully be greater than last year. The hives are full of bees, the Queens unclipped, with two thriving colonies filling their home with honey. We will share with them at the end of the summer, leaving them plenty to overwinter, just taking what is spare to seal into jars.

I’m surprised to find that two trees of Marjorie Seedling are full of plump, sweet plums, ready to pick. Plums from my childhood ripened only at the very end of the summer, days marked with memories of sunshine, wasp stings and sticky fruit.

It seems too early to find any trees that might be ready. The wasps are doing their best to secure the majority of the dark purple and blushed fruits for themselves. These trees are full of fruit. The Denniston Superb and Yellow Pershore though are far from ripe. The Denniston is a greengage, quite large, very round and as I remember from last year, very sweet. Much larger than the French Reine Claude, (seemingly the benchmark for greengages), though these last few days they remain solidly unripe.

I ate one.

The acidic twang poked me in the back corner of my jawbone, clenching my teeth together as they squeezed the sharp juice from the plums, reminding me that I should really have left it on the tree. The Pershore is a different plum, a beautiful golden elongated oval-shaped fruit, but again they will not be ready for some time yet. Ouillings Golden Gage is another that quite frustratingly announces it’s far too early to pick when I bite into it.

There is an old planting map from the time these trees were established all that time ago. It sort of makes sense today, though I find it a little difficult to decipher as over time there have been trees felled through disease and then some new ones planted without record, but with an hour or so one-afternoon late last autumn I mostly made sense of the lines of intriguing names and numbers. I’m still confounded by the western corner as frustratingly it makes little sense and there are about eight trees that are a mystery. John can’t seem to remember either. It doesn’t really matter though. With the abundance of what we have here, we can only count ourselves lucky. I can only hope to do this perfect fruit justice through my work.

The Winter Gem and the Blenheim Orange are the two apples that stood out for me last year. We harvested about two-thirds of the orchard which was approximately one tonne of apples, juicing the majority for the coming year and with a decent amount set aside to ferment into cider that I spent the autumn and winter nurturing into cider vinegar. We created three apple juices, the first was a small bottling of the Winter Gem, a highly perfumed, small, bright red apple, the juice so floral it’s quite staggering. The Blenheim Orange was the second single pressing, again wholly different from anything I could compare it to on the farmers market shelves. The remainder, well over half a tonne of different apples, was blended into one juice and when poured showed a blushed pinkish-green cloudy juice.

The cider was created from the blend, the vinegar took about five months to turn from a cloudy alcoholic vat of cider to a brightly golden clear acetic acid. The flavour is sharp and apple-like, unlike cider vinegar from the shop. It has been my staple vinegar this last year, used as a base to be flavoured by leaves, flowers and fruits. I look forward to making a lot more later this year.

Plums were turned into jellies, jams and cordial. I made pots of plum and smoked garlic chutney for cheese, some of which I served along with the farmhouse cheddar that I made at the end of last year. I still have a few bags of Yellow Pershore in the freezer that I occasionally top up the cordial bottles with when running low. They make such a delicious drink when left to simmer in syrup with vanilla pods and lemon peel.

The heavy pruning of the orchard was done in the depths of last winter, the frost-covered trees dormant, bathed in the cold blue light of the coldest months. Carefully pruned over a few weeks, each branch and burr was selected and examined before being carefully snipped with sharp steel secateurs, a small saw for the heavier branches. Trees that looked so abundant with leaves and fruit only a few months earlier, now standing awkwardly in the cold, like a schoolboy with a drastic haircut on the first day of term.

The blossom came early this year, delicate shades of pink and white petals that showed the bees where to feed, though for only the briefest time. Then comes the bud break, the unfurling of all that potential within. The harvest this year will be bigger than last it seems. The pruning has helped the trees enormously. One obscure little pear tree, the Beurre Hardy last year managed to give only a handful of pears, mostly tiny and shrivelled. This year there are dozens of fine small fruits that will hopefully shed some light on their beautiful name.

It is still summer so there is still plenty of time to consider what will be done with that harvest. Most likely batches of vinegar. I’ll fill the larder with preserves, ferments, chutneys and jam. I’ll make juices, cordials and perhaps some pear cider. The last time I was in Florence I tried a pear-flavoured pecorino, so there is definitely an experiment there to test my cheesemaking skills.

This piece was supposed to be for my paid subscribers, but after reading through I have decided that it should be for everyone. My newsletter celebrated a milestone this week, so due to all of the new people reading, an extra newsletter seems appropriate.

I’ll post some extra content for all my paid subscribers over the weekend.

A big thank you to all of the new subscribers this week. I hope you enjoy my words.

Until then,

William

Bees and an orchard - it's a magical combination!

Thanks for the tour of your orchard. Old apples have such lovely romantic names. Years ago I wrote a magazine story on heirloom apples, which sent me down a rabbit hole exploring old Southern (U.S.) apples. Now I’m jonesing for apple pie even if it’s only July.